City of Rochester’s Darin Ramsey (second from the left) shows summit participants how Rochester's new dedicated lanes and protective bollards provide a much safer path for cyclists.

By Robin L. Flanigan

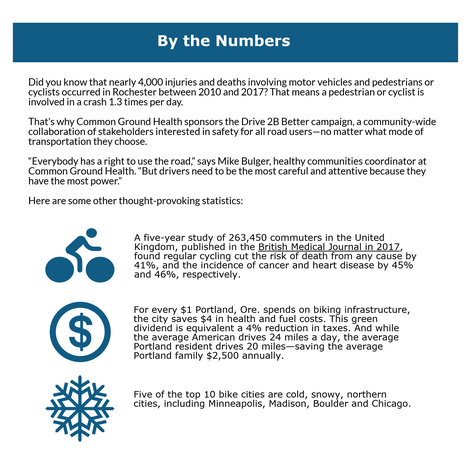

Could crosswalks, protected bike lanes and other traffic safety features combat chronic illness, control weigh and improve mood?

The data says yes.

“There’s good evidence we should be active, and we aren’t,” says national public health, planning, and transportation consultant Mark Fenton, citing a Centers for Disease Control statistic that only 23% of Americans get enough exercise. “Telling people to exercise doesn’t do it. What does seem to matter is changing the environment, and active transportation seems to be an instrumental piece of that.”

Think of active transportation—such as walking and biking—as any people-powered mobility method.

Fenton served as keynote speaker for Common Ground Health’s active transportation summit held in Rochester in late May. Titled “Community Design for the Triple Bottom Line: Economic, Environmental and Public Health,” the summit highlighted advances in street design, transportation networks and additional areas that can make it easier to walk and bike.

The current standard for good street design is about how quickly cars can move from point A to point B. Unfortunately, that type of development generally comes at the expense of pedestrians and cyclists. At the summit, planners from across the region and others took workshops and moved around downtown—on foot and by bike—for an up-close-and-personal look at what makes for smarter streets.

In this case, smarter streets are complete streets, characterized by their designation as safe for all users—pedestrians, bicyclists, motorists and transit riders of all ages and abilities.

“I’ve talked to residents who don’t feel comfortable going to the nearest grocery store because they have to cross a busy street and drivers aren’t watching out for pedestrians,” says Mike Bulger, healthy communities coordinator at Common Ground Health.

Best practices in contemporary planning and design—a combination of education, engineering and enforcement—solves this sort of problem and so much more.

Active transportation has far-reaching environmental, economic and social impacts as well. Reduced dependence on automobiles lowers greenhouse gases and other air-quality emissions, minimizes motor vehicle-related injuries and deaths, and supports development of vibrant cities, as well as offers much-needed access for those experiencing poverty.

If cold-weather cities in places like Minnesota and Wisconsin can embrace an active transportation lifestyle, so can the Rochester region.

What’s necessary to achieve the same outcome, however, is better cross-sector collaboration.

“We have silos between the Department of Health and the Department of Transportation, and the two are intricately connected,” says Scott MacRae, MD, board member of the Rochester Cycling Alliance, who bikes the six-mile ride to work at least 10 months a year.

Adds Bulger: “This isn’t just a public health issue, it’s not just a street design issue, and it’s not just about an individual decision. It’s really about all of these different groups working in concert, having a shared vision. It’s about turning a hard choice—whether to walk or bike—into an easy choice.”

MacRae points to the the Vision Zero Network as a model for how cities should approach traffic problems that contribute to the deaths of more than 40,000 Americans —and the injuries of thousands more—annually. First implemented in Sweden in the ‘90s, the road traffic safety project, which aims to achieve no fatalities or serious injuries involving road traffic, has proven successful across Europe and now is gaining momentum in major U.S. cities nationwide. It has yet to come to Rochester.

Functional, traffic-calming measures that encourage active transportation also may invigorate struggling neighborhoods. According to a study conducted by the League of American Bicyclists, people on bikes are more likely to make repeat trips to local stores, which can increase business.

Fenton, an adjunct associate professor at Tufts University's Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy, and former host of the "America's Walking" series on PBS television, believes targeting one type of bicyclist in particular would reap the greatest rewards.

That is the “interested but concerned” demographic, one of four types of bicyclists originally described by Roger Geller, bicycle coordinator at the Portland Bureau of Transportation. This group is willing to ride only with the guarantee of high-quality bicycle-specific infrastructure.

“About 60% of people are ‘interested but concerned,’ and that’s a monstrously big deal,” says Fenton. “That suggests they’d bicycle more if they had more confidence about getting safely from their place of origin to their destination.”

During the summit’s bicycle tour, participants learned about street design improvements to create bike paths, from dedicated lanes marked by a solid line or protective bollards, to the new two-way, off-street path constructed as part of the Inner Loop redevelopment project.

They also heard about a City Council decision not to build an off-street cycling lane along Main Street, in favor of a more cost-effective but less protected on-street lane. For subsequent projects, however, when residents have advocated for more protected lanes, City Council has approved the additional spending.

The takeaway? Residents shouldn’t underestimate the power of a vocal community.

“They need to find out how to [be] engaged locally, to be a role model,” Fenton says. “That could be enough to elicit change.”