By Robin L. Flanigan

It’s time for the 2020 Census.

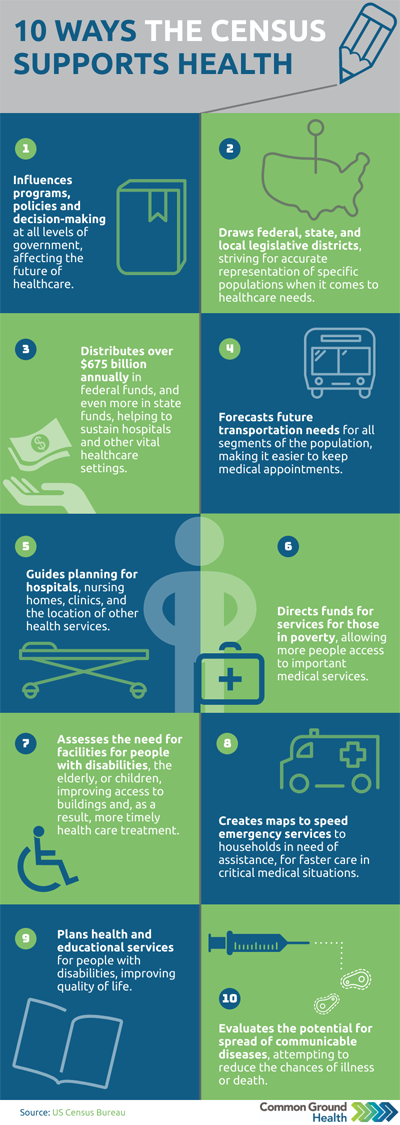

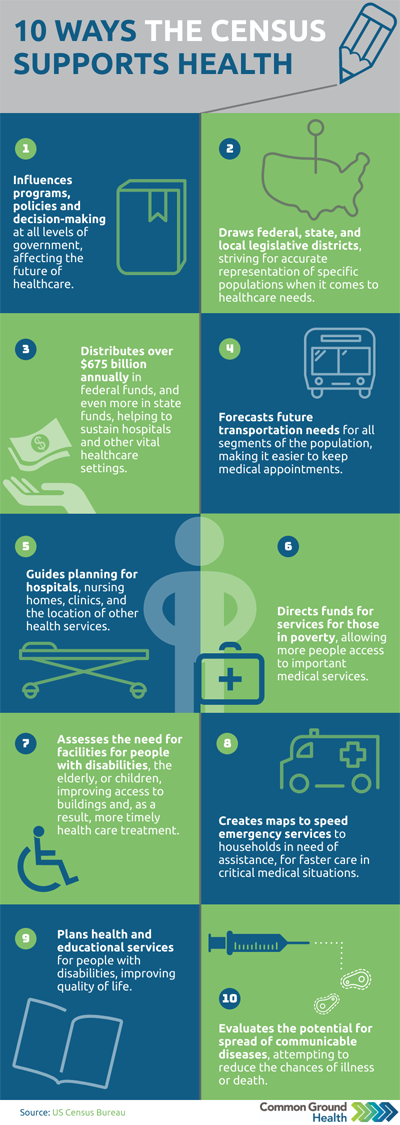

Once every decade, the U.S. Census Bureau leads an attempt to count every person living in this country—a massive undertaking with far-reaching implications for how health care is delivered in the Finger Lakes region and beyond.

“The census collects a wealth of demographic data including age, race/ethnicity, income, housing status and more,” says Catie Kunecki, a health planning research analyst with Common Ground Health. “Having this information helps to create more relevant, culturally appropriate, and effective health improvement initiatives.”

In fact, the numbers underlie a significant portion of the data Common Ground Health uses in its work, such as population estimates, disease rates, and other public health research.

Nationally, every year, the federal government distributes more than $675 billion to states and communities based on census data—money that supports programs such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (also called SNAP), the National School Lunch Program, and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP).

The figures also determine how many representatives each state gets in Congress, and are used to redraw district boundaries.

“If there is representation based upon the true population within state, you have people fighting for you and what your community needs,” says Jeff Behler, director for the New York Region of the U.S. Census Bureau.

For health centers like Finger Lakes Community Health, those needs can be met in part through grants. The federally qualified health center uses grant money—applied for using census data—to fund interpreters, a critical service given to patients who prefer to be served in their native language. One-third of its clients are agricultural workers—and 90 percent of them are immigrants. The languages they speak include Spanish, Haitian Creole, and several other indigenous languages.

The challenge, however, is in getting the workers to make themselves counted. Although their data is not shared with federal immigration officials, they harbor a deep fear that it will be someday.

“With the political situation right now and so many laws going into place, there are people who do not want to say, ‘Here I am,’” says Beverly Sirvent, director of the agency’s agricultural program.

Sirvent uses this rationale when explaining to them that being proactive is in their best interest: “As a protection, if you fill out [the census form] now, census workers won’t go looking for you later.”

The Census Bureau has had challenges getting an accurate picture of other populations as well.

In the past, minorities have been undercounted because they disproportionately live in hard-to-count circumstances, the Census Bureau has said. Children under the age of five increasingly are left out of official census responses.

Behler offers this analogy to drive home the consequences of undercounts: “Imagine you have a school of 100 kids, and let's say only 80 kids get counted for one reason or another. For the next 10 years, that school is going to receive 80% of the funding it deserves. And that doesn't just affect the 20 kids who weren’t counted—it affects all 100. Now apply that to a neighborhood, or a community health center. That's why it's so important we get the most complete count.”

The 2020 Census comes at an important time, when this country’s increasingly diverse and growing population needs effective health care, education, transportation, public policy, and other systems more than ever.

As Sirvent says: “It’s not just that you need to be counted, it’s why you need to be counted.”

Every household will have the option of responding to the census online, by mail, or by phone.